|

| Click images to enlarge. |

Pages

▼

Thursday, July 30, 2015

Tuesday, July 28, 2015

Two views of Lummus Park in the 1930s

Monday, July 27, 2015

Friday, July 24, 2015

Wednesday, July 22, 2015

South Florida beauty pageants in the 1930s and '40s

Vintage British Movietone newsreel of the 1941 Miss Florida beauty pageant held at the Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables on Feb. 23, 1941.

1941 Miss Florida pageant

Newsreel of a lifeguard "beauty contest" at Miami Beach ... probably from the late 1930s.

Videos via British Movietone's YouTube channel.

Tuesday, July 21, 2015

Monday, July 20, 2015

Dodge Island - 1968

Miami News, Jan. 17, 1967: New $22 Million Port 'Shapes Up' Here

|

| Dodge Island, 1968, with MacArthur Causeway, Palm Island and Miami skyline. (Click here to enlarge) |

Friday, July 17, 2015

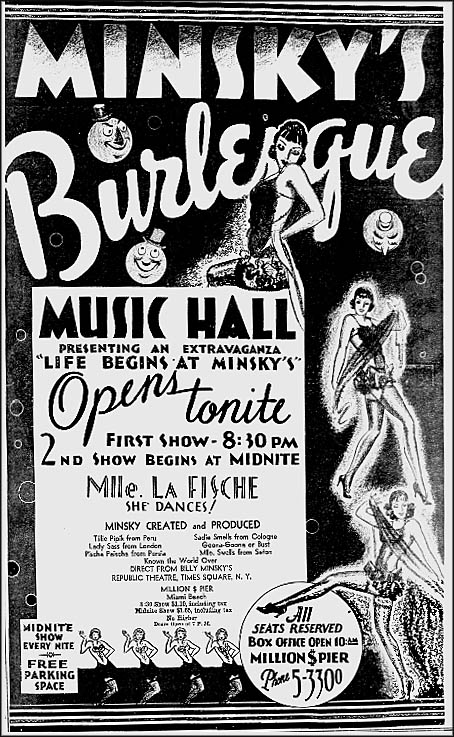

Minsky's, Miami Beach's most popular strip club, was located on a pier

|

| Carter's Million Dollar Pier and Dixie Bath House, 1934. |

|

| Miami Daily News, Jan. 18, 1935. |

|

| Miami Daily News, Feb. 2, 1935. |

Miami Daily News, Jan. 18, 1935: New Attractions Mark Opening of Pier Tonight

|

| Miami Daily News, Feb. 18, 1937. |

|

| Miami Daily News, March 24, 1942. |

BUILT IN BOOMTIME, BEACH PIER TO BE DEMOLISHED AS AN EYESORE

Miami Herald, November 22, 1984

by PAUL SHANNON Herald Staff Writer

Miami Beach's landmark South Beach pier, imbedded firmly in the memories of thousands who fished off it or danced on it during the past 60 years, will be demolished within 15 days, the City Commission decided Wednesday.

Ignoring an emotional plea from a local preservationist, commissioners unanimously approved spending $112,000 to tear down the pier -- twice the cost of building it in 1926. The aging pier is dangerously decayed and an eyesore, they agreed.

"The city can build another pier anytime," Mayor Malcolm Fromberg said.

Preservationist Nancy Leibman said such reasoning misses the point.

"I realize that the demolition is a fait accompli," she said, "but I just had to come back to try and raise the commission's consciousness of the obliteration of the city's past."

The pier is part of the city's heritage, she said.

"It is one of the reminders of the past that give us a sense of belonging in a community," she said. "It is part of the city's soul. I hope we are not so desperate for development that we would destroy the soul."

For Liebman, the commission modified the contract won by Cuyahoga Wrecking Co. before approving it. If possible, they will save the Pier Park sign that graces the pier's entrance.

"That's why we are currently in litigation with Miami Beach," said Ivan Rodriguez, Dade Historic Preservation Board director. The county board is suing the city to force it to buttress a preservation ordinance known as the weakest in the country. "The pier is quite irreplaceable."

"I can't think of a city with a worse track record of preservation," said Michael Zimny, historic site specialist for Florida's Division of Archives. In the past two years, the city has approved the destruction of three blocks of Art Deco hotels, its streamline moderne Sheridan Theater and its only surviving red brick and Dade County pine warehouse.

"The eyes of the city seem to be continually closed to its own history," Zimny said.

The pier, a concrete walkway flanked by a bandshell and dance pavilion jutting across the man-made beach where Ocean Drive and Biscayne Street come together, was built in the early 1920s by flamboyant casino owner and fight promoter George R.K. Carter. He put a two-story building on the pier's tip to house what became the city's most popular strip joint, Minsky's Burlesque, and he called it Carter's Million Dollar Pier.

Minsky's was knocked down by a runaway barge during the 1926 hurricane, and the pier became known for fishing and outdoor evening dances. When the city took over the pier in the 1950s, razing the honky-tonk bars at its entrance and proclaiming it Pier Park, the dances drew more than 1,000 revelers a night.

Indeed, the pier was touted as "demonstrating the city's eternal pledge to give tourists of all ages and inclinations a happy holiday on Miami Beach."

The city stopped maintaining the pier in 1973, when it was to be demolished under the old redevelopment plan condemning everything south of Sixth Street. When the plan was officially dropped more than a year ago, the pier became a hangout for drug dealers.

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

James H. Snowden residence, Miami Beach - ca. 1917

|

| Miami Beach home of Oklahoma oil millionaire James Snowden in 1917. The home was built on a desolate stretch of sand on Miami Beach near what is now Collins Ave. and 44th Street. Click here to enlarge. [via Miami Beach Digital Archives.] |

In 1923, Snowden sold the residence for $250,000 to Harvey S. Firestone, founder of Firestone Tire and Rubber Company.

In 1952, hotelier Ben Novack purchased the Firestone estate and announced plans to build a 554-room, $14,000,000 hotel on the site.

Work started on the Fontainebleau in January, 1954 and Firestone's estate was used as the contraction office.

|

| Miami Herald photo by Bob East. (1954) Click images to enlarge. |

|

| 1954. |

|

| 1955. |

Curbed Miami: In 1955, the Fontainebleau Hotel Was Irrepressibly Glamorous

Tuesday, July 14, 2015

Vintage cruise ship postcards

Monday, July 13, 2015

Friday, July 10, 2015

The McAllister Hotel was Miami's first high-rise hotel

|

| Miami Daily Metropolis, Jan. 18, 1920. |

THE MCALLISTER WAS CITY'S FIRST HIGH-RISE HOTEL

Miami Herald

December 3, 1987

The McAllister Hotel sits empty, windows broken out, hallways still, lobby bustle-less, ghosts its only guests.

What was Miami's first high-rise hotel and once the city's largest is reduced to waiting for a raze in a paint job that manages to combine the color brown with those of bottled Thousand Island and French dressings.

It wasn't always so.

In 1912, Emma Cornelia Hatchett McAllister, a wealthy widow from Fort Gaines, Ga., bought a half-block of bay-front property at Flagler Street and Bayshore Drive.

It was not until 1926 that Bayshore would be renamed Biscayne Boulevard, bay bottom sand would be sucked up to fill in Bayfront Park, and the corner would find itself as the central intersection of downtown Miami.

The widow decided to build a hotel there in 1915. Royal Palm Park was across the street to the south. A three-story, clapboard home was to the north. The Elks Club was just down Flagler to the west. And to the east was Elser Pier, sandy beach and the lapping waters of Biscayne Bay.

Concrete was poured in 1917. By 1919 seven stories were up when the widow McAllister ran out of money.

New owners arrived and the show went on, and in 1920 , during the post-World War I boomlet, the hotel, named for madam founder, opened its first of three wings for the winter season. It was spectacular.

The ground floor contained street-level shops with striped awnings. Second and third floors were shaded porches where guests could sit in rockers and take in the breeze off the bay. Potted palms, tile floors.

Later, the new hotel was so popular that it had a problem keeping towels. Guests liked to steal them, using towels to cushion bottles of bootleg liquor, readily available in Prohibition Miami after being smuggled in from Cuba and the Bahamas. Management began offering corrugated cardboard for guests with a taste for wrapping.

In its heyday, the hotel used 4,800 towels one month and spent $15,000 a year to replace soap in rooms. A third wing was finished in 1925. Finished, the McAllister had 10 floors, 550 rooms. For the 1927-28 season, advertised guaranteed rates were $6, $8 and $10 for a single and $8 and up for a double. European plan, meals not included.

City leaders decided they wanted a boulevard named Biscayne in front of the McAllister . They proposed filling in the beach front, creating a park. The hotel 's owners were not amused. They fought the idea.

The city promised to outlaw buildings on the park side of the street. Eventually, the hotel gave in. Its frontage, just 50 feet from the beach, was gone. It was suddenly moving inland. By 1926, its fortunes were moving in decline.

The park was built, and in 1933 Franklin D. Roosevelt was set to make a speech there, joined by Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak. McAllister porches were jammed with people who witnessed the near assassination of the president-elect and the death of the mayor.

During World War II, the Navy took over, using the hotel as a billet for enlisted men. There went the neighborhood from 1942 to 1945.

|

| Undated photo of the McAllister Hotel under construction. (Note notations in margins) Click here to enlarge. |

|

Aerial view of downtown Miami with new

|

|

| Miami Daily Metropolis, Jan. 10, 1920. |

|

| Miami Daily Metropolis, Dec. 30, 1920. |

|

| 1923. |

|

| McAllister Hotel with cars parked on sand. (1925) Click here to enlarge. |

|

| 1926. |

|

| Looking west on Flagler Street. McAllister Hotel is in center of photo. (1931) |

Thursday, July 9, 2015

Morris Lapidus: 'I wanted people to walk in and drop dead'

Via the New York Times:

No American architect in the 20th century embraced more flamboyantly the flagrantly commercial aspect of design than did Morris Lapidus, who titled his autobiography "Too Much Is Never Enough."

Lapidus (pronounced LAP-i-dus), who died at age 98 in 2001, was long derided but later praised for designing some of South Florida's gaudiest, glitziest and most glamorous hotels — including the Fontainebleau, the Americana and the Eden Roc — in the 1950s and 1960s.

His style was mockingly called Miami Beach French, and critics scorned the ''obscene panache'' with which he created what they called his palaces of kitsch, many of which have been razed or remodeled. But as Miami Beach underwent a renaissance, becoming a trendy place for the jet set, the critical winds blew in his direction. After being shunned by architecture critics and architects for much of his long career, he and his work are now referred to with respect by a new generation of writers and postmodernist architects — among them Rem Koolhaas and Philippe Starck. He had been, several critics decided, ''a postmodernist long before the term existed.''

Lapidus was steeped in classical architecture, but he created an eye-catching mixture of French Provincial and Italian Renaissance — with whiplash-curve facades and a splashy use of color — and he lavished ornament upon ornament. His most famous work was the Fontainebleau, built in 1954. Its interiors combined 27 colors. It had what was called a staircase to nowhere that actually led to a modest cloakroom, so that dinner guests could leave their coats and parade down in their sparkling jewelry and decolletage to the delighted stares of the crowds in the hotel's lobby. The hotel was once called ''the nation's grossest national product.'' But Lapidus dismissed all critical jibes. He proudly referred to the Fontainebleau as ''the world's most pretentious hotel.''

Architectural understatement was not his style. He put live alligators in a terrarium in the lobby of the Americana, he said, so that guests would ''know they were in Florida.''

''I wanted people to walk in and drop dead,'' he said of his celebrated hotel lobbies. His work, he said, ''set new standards, and a lot of old-line critics didn't agree with me.'' By the 1980s, though, he said, that had changed, ''because everyone is doing the unusual now.''

Curbed Miami: Old Photos Show the Fontainebleau Like the Stage Set it Was

Miami Archives: From Millionaires' Row to Hotel Row

Wednesday, July 8, 2015

Beepers and pay phones in Casablanca

While doing some research recently, I stumbled upon one of my favorite Miami Herald Tropic magazine articles from 25 years ago. (Remember Tropic magazine?)

"Welcome to Casablanca" by John Dorschner, ran on Sunday, June 15, 1986.

In the piece, written five years after the infamous Time magazine "Paradise Lost" cover story and 3 years after "Scarface" came to town, Dorschner attempted to show how 80's Miami had become, for some, a modern day Casablanca. However, in this remake, Crockett and Tubbs and more than a few Colombian drug dealers, replaced Bogart and Bergman.

Back then, if you knew what to look for, the drug dealers weren't all that hard to spot. They did everything except wear uniforms with name tags.

But the tools of their trade - beepers and pay phones - seem downright quaint today. In some circles, just wearing a beeper meant you might be a drug dealer. (In the 1986 trial of "Miami River cop" Armando Estrada, another officer testified that he had seen Estrada "wearing a beeper.")

In one section of his 1986 Tropic story, Dorschner painted a fascinating picture of the stereotypical 80's drug dealer and drug deal. It's safe to say this is not how drug deals are conducted today.

"Welcome to Casablanca" by John Dorschner, ran on Sunday, June 15, 1986.

In the piece, written five years after the infamous Time magazine "Paradise Lost" cover story and 3 years after "Scarface" came to town, Dorschner attempted to show how 80's Miami had become, for some, a modern day Casablanca. However, in this remake, Crockett and Tubbs and more than a few Colombian drug dealers, replaced Bogart and Bergman.

Look at us now. Awash in crime, still. Aswarm with immigrants. Aboil with fear. And we are . . . Casablanca. They call it exotic intrigue. Romance. Multicultural excitement. This town has become a movie. Or more precisely: a TV show.One of the problems Miami faced 25 years ago was a flourishing drug trade.

You can trace the image back four years, to the time that a television producer named Tony Yerkovich visited Miami. Yerkovich traveled around the town with undercover agents and visited nightspots with "guys on the other side of the law." He heard about dope dealers, gun smugglers, "propagandists for foreign governments," corrupt bank officials, exiled dictators and intelligence agents. Miami, he concluded, was "a modern-day American Casablanca."

Miami-Casablanca : The idea had been floating around since the '60s, mostly cropping up in minor magazine pieces, but Yerkovich was able to convert his vision into truly pop culture. His Miami Vice had banal dialogue and trite plots, but the show achieved a certain look, a feel. Suddenly the show was "hot."

Hordes of out-of-town journalists -- from the London Mail, Sacramento Bee, Paris Match, Dayton Daily News -- have been descending upon Miami, intent upon finding the . . . real story. "There had to be a hundred people doing 'the real Miami Vice,' " says Billy Yout, spokesman for the Miami office of the

Drug Enforcement Administration, who was interviewed by most of them.

When a Norwegian newsman suddenly showed up and asked an undercover Metro agent if he could follow him around for a day, the agent asked if Norway was about to start broadcasting Miami Vice. Yes, said the newsman, how did you know?

Back then, if you knew what to look for, the drug dealers weren't all that hard to spot. They did everything except wear uniforms with name tags.

But the tools of their trade - beepers and pay phones - seem downright quaint today. In some circles, just wearing a beeper meant you might be a drug dealer. (In the 1986 trial of "Miami River cop" Armando Estrada, another officer testified that he had seen Estrada "wearing a beeper.")

In one section of his 1986 Tropic story, Dorschner painted a fascinating picture of the stereotypical 80's drug dealer and drug deal. It's safe to say this is not how drug deals are conducted today.

THE COIN DROPPERS

It's quite easy to see a drug deal happening in South Florida. They're going on all around you, especially if you live in the southern suburbs. All you have to do is know what to look for.

Many dopers still deck themselves out in gold, with the Rolex watch and the Porsche convertible. But others, realizing the stereotypes, are toning themselves down when they go out working.

"Colombians are not overdressed," says Detective Marty Heckman, who -- like Belker on Hill Street Blues -- spends much of his time "hanging out," usually in Kendall shopping centers. "They're suave but not flashy. They like color-coordinated clothes -- if they have gray slacks, they'll have gray shoes. They're all like 5-8, 145-150 . . . beeper on the hip. And they linger by the pay phones, with expensive little black books with all sorts of codified numbers."

The beeper -- usually the digital-readout kind -- is their tool of the trade, such a giveaway that some dopers have started hiding theirs in ankle holsters.

Dope deals are always fluid, perhaps a dozen conversations and meetings, none of which lasts more than five minutes. Doper one beeps doper two to call him at a pay phone. Doper two does so, from another pay phone. Beeper to beeper, pay phone to pay phone, calls virtually impossible to trace. "Coin droppers," detectives like Heckman call them. Men who spend their days hanging around pay phones, usually in Kendall, because that's where most dopers live, and because they often are carrying considerable amounts of cash and they feel more certain they won't run into a random mugger in staid Kendall.

"Miller Square used to be a mecca for them," says Detective Heckman. "At 137th and Miller. But then the uniformed officers started hanging out there in the green and whites, and 'they scared the fish from the bay.' "

Billy Yout at DEA says dopers also like the bank of pay phones beside the Winn-Dixie in the Midway Mall center. Sometimes agents have seen dopers three deep at the phones, waiting for an available line. Dadeland is popular, and the Falls, and gas-station/convenience stores -- any pay phone where there is a large field of view, so that the dopers can check to see if they're being observed.

If you want to spend a little time, you can watch a deal taking place, or at least part of the negotiations. Look for luxury cars -- say, a Mercedes -- parked beside a Kendall pay phone. Or a rental car (rental cars have license-plate numbers beginning with Z), because there's a trend for dopers to seek the anonymity of a bland Oldsmobile rental.

What you see would go something like this scene, witnessed by a journalist on a weekday afternoon:

On Southwest 117th Avenue, a little north of Sunset Drive, a two-tone Lincoln was parked in front of a Farm Store. At a pay phone, a man was dressed casually, in black boots, nondesigner jeans, a loose-fitting Hawaiian shirt. He was wearing a subdued gold-and-steel watch that appeared to be a $1,500 Concord model. He was chatting in a slow, dignified Spanish, using the formal "usted" manner of address.

When the journalist approached and picked up the adjoining pay phone, the man spoke quickly and hung up. A minute later, a beige Mercedes appeared. The Lincoln man walked over and slid into the passenger seat in front.

The Mercedes drove across the street. Three minutes later, it was back, and Mr. Lincoln climbed out, said goodbye to Mr. Mercedes and drove off in his own car.

The "meet" was over.

"That's a perfect profile of a narcotics meet," said Metro narcotics specialist Reddington, when told of the meeting. "That is so common, around any shopping mall in Dade County. More so in the southwest, but it happens all over. . . . It doesn't take a sixth grade education to see that he's not playing the stock market."

.jpg)

.jpg)